Election returns for the Democratic primary for mayor of New York are still coming in but I couldn’t wait to plug the numbers we already have into my spreadsheet. Although I generally like to think about my opinions for one to two decades before posting them on the Internet, I’ll make an exception for the most stunning election night in New York City in 24 years. (Remember that number for later.)

I’ll need more time with the data but my kids are only at camp for a few hours so here are my initial reactions from last night.

Ranked-choice voting isn’t going to matter in 2025. This election seemed like the perfect setup for strategic ranked-choice voting: two polarizing candidates running far ahead of a pack of inoffensive, qualified second-choices. Ranked-choice voting allows voters to rank up to five candidates in order of preference so the number of total ballots that rank a candidate can be as important as the number of voters who rank a candidate first—broad appeal should matter as much as intensity of support.

In theory, RCV provided an opportunity for voters who absolutely didn’t want either Andrew Cuomo or Zohran Mamdani—what I’ve privately been calling the Nozonocuo voter, mainly because Nozonocuo is so fun to say—to elevate a third candidate who was also acceptable to (i.e. ranked by) Cuomo and Mamdani voters.

But that premise turned out to have been based on a flawed assumption. There was only one truly polarizing candidate—Andrew Cuomo—while support for the other, Zohran Mamdani, was both intense and broad.

Anti-Cuomo consolidation happened early. In 2021, it took many rounds of ranked-choice voting for the anti-Eric Adams vote to come together. This time, Zohran Mamdani captured the vast majority of anti-Cuomo sentiment—the DREAM vote—in the first round. Whether this is entirely a reflection of Mamdani’s strength as a candidate or voters still preferring binary choices in an election remains to be seen.

2025 didn’t look as different from 2021 as it seems—with one notable exception. I recently argued that the path to winning the Democratic primary ran through middle-class and working-class Black neighborhoods. Let’s first take a very quick look at the rest of the city, which this year has so far made up 77.4% of the electorate, compared to 74.5% in 2021. (All of the 2025 data is as of June 25, 2005 at 12:33 AM, the most recent update on the NYC Board of Elections website at the time I’m writing.)

The results in this roughly 3/4 of the city were actually not that far off from 2021, at least after the first round of voting. Cuomo ran ahead of Eric Adams here, ranked first by 34.3% vs. 23.1% for Adams. Mamdani won 44.1%, compared to a combined 45.1% for Kathryn Garcia and Maya Wiley. (Brad Lander won 13.5%, less than Andrew Yang’s 14.5% but likely to go mostly to Mamdani in RCV.)

I’ll have to go back through the numbers more closely after the entire cast vote record is available in July but my first reaction is that the distribution of votes in most of the city didn’t change quite as much between 2021 and 2025 as I can almost guarantee the popular narrative will suggest it did.

That’s not to say Mamdani didn’t improve on the performance of the liberal/progressive candidates in 2021. This year, the progressive bloc will make up a greater percentage of a larger electorate—turnout was higher—while the anti-progressive bloc is smaller than last time. Mamdani also ran quite strong in the “neither” bloc of Upper Manhattan, Chinatown and Asian communities in Queens. And that all may have been enough after ranked-choice voting for Mamdani to withstand Cuomo’s strength among Black voters, except…

Cuomo was weaker in Black neighborhoods than expected—and Mamdani was much stronger. My advice that progressive voters “should rank the entire progressive slate...but base the order of their rankings on which candidate is most likely to do best among the city’s more moderate Black voters” was good counsel, I think. What I got wrong was which candidate that would be.

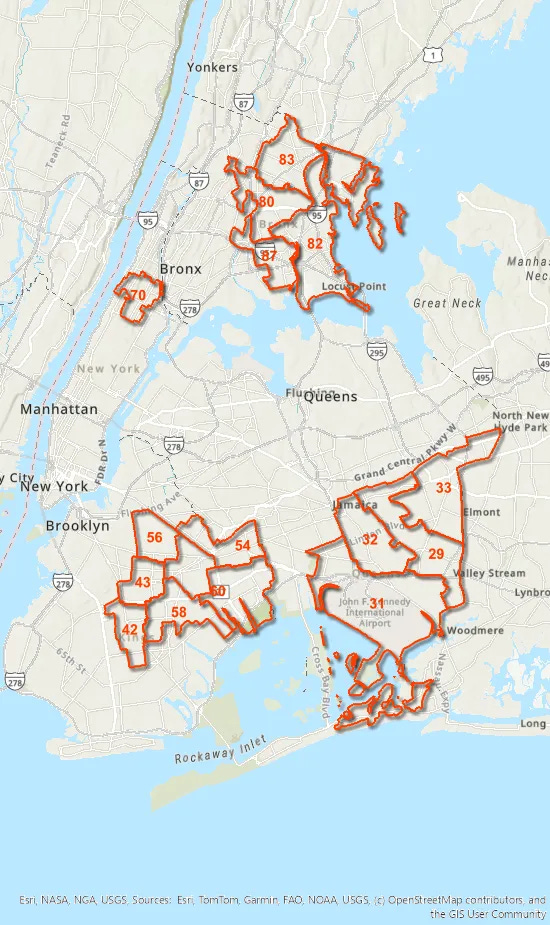

A smaller portion of total votes in 2025 came from majority-Black neighborhoods in central Brooklyn, southeast Queens, Harlem and the northeast Bronx than in 2021 but a lot more of those votes went to Zohran Mamdani than my own prior assumptions led me to believe was possible. Andrew Cuomo is running ten points behind Eric Adams in these communities—the not-entirely-unpredictable shortfall that I thought would create an opening for a progressive candidate—but Mamdani was ranked first by 41.6% of the voters here, nearly doubling Maya Wiley’s returns from 2021.

If Cuomo had matched Eric Adams’ numbers—as a lot of the polling thought he might—and Mamdani had performed more like a traditional progressive, we’re probably going into ranked-choice tabulation closer to a tied race. There’s a lot to think about here but Mamdani’s success in middle-class and working-class Black neighborhoods implies that voters there might not be as uniformly “moderate” as many of us—including many of their political leaders, who overwhelmingly supported Cuomo—might have thought.

Cuomo’s relative weakness among Black voters—his presumed base—also devastates any rationale for him to stay in the race as an independent candidate. We should know more soon: acording to the political calendar issued by the state Board of Elections, Cuomo has only until this Friday, June 27, to drop Fight and Deliver, the ballot line he formed based on a never-produced movie about Jaime Escalante teaching calculus students how to box.

Mamdani’s win shouldn’t be a total surprise. Cuomo ran an almost shockingly lackluster campaign and Mamdani appears to be a singular political talent with a growing movement behind him, which was enough for a few smart commentators to predict a Mamdani win. But history also tried to tell us what was coming.

All the way back on May 5, I promised to share “my theory that history strongly hints that this will be a generationally important election for New York.” Now that it conveniently looks like my theory will be right, I can finally tell you what it was.

For reasons known only to numerologists and astrologers, every 24 years New York elects a mayor who fearlessly pivots away from their presumed political identity to build a durable coalition that will define city politics for an entire generation. Let’s call it the Vigintiquadrennial Theory of Mayoral Politics, or the VTMP.

I might not have been able to tell you that Zohran Mamdani was going to do so well on Election Day that Andrew Cuomo would concede before the ranked-choice counting even kicked in, but an unscientific survey of the last century of elections gave me the idea a while ago that 2025 was likely to usher in a new era in New York.

Very young, extremely progressive, and exceedingly charismatic, Mamdani certainly looks the part of a potentially transformative mayor. But what defines the mayors of the VTMP isn’t how they won their elections but how they maintained their power.

Our story begins in 1929, when Fiorello La Guardia became the Republican nominee for mayor. La Guardia, every mayoral candidate’s favorite answer to “who’s your favorite mayor," wasn’t actually elected until 1933 but he established the signature move employed by his most electorally-successful succesors: a subversion of expectations about how they’d govern—and with whose support.

La Guardia was a Republican who became the most beloved mayor in the city’s history through his alliance and partnership with Democratic President Franklin Roosevelt.

Elected in 1953, Robert F. Wagner, Jr. was the handpicked candidate of Tammany Hall, the Democratic machine in Manhattan, but then turned on Tammany and brought the reform wing of the Democratic Party into his political fold.

In 1977, Ed Koch was a liberal Congressman from Manhattan who enthusiastically embraced conservative positions and language, supported Ronald Reagan and ran for his first re-election with the support of both the Democratic and Republican parties.

And 24 years ago, in 2001, Mike Bloomberg was a billionaire Republican who would eventually win the support of white liberals in Brooklyn and Manhattan, Black voters in Brooklyn and Queens, and almost all of organized labor—New York is more likely to elect a socialist before another Republican wins 58% in a citywide vote. Oh, wait.

The circumstances under which these mayors first won their elections were unique, as were the issues that dominated their campaigns and the policies they pursued once in office, but it’s not a coincidence that La Guardia, Wagner, Koch and Bloomberg were the only three-term mayors in the history of New York. For almost half of the last century, one of these four men has been mayor.

There are term limits again now so Zohran Mamdani isn’t on the fast track to twelve years in City Hall, but if he wants to keep this streak of major mayors going, there are valuable lessons to be learned from his vigintiquadrennial predecessors.

A 24-year cycle makes a certain amount of intuitive sense—every generation will eventually demand their own political leadership. But the success of that leadership—its political durability—is not guaranteed. Zohran Mamdani was the most progressive candidate in this race—in any mayoral race in New York in recent memory, in fact—and one cannot dispute that his victory in the primary is an endorsement of his vision and policy agenda. What made La Guardia, Wagner, Koch and Bloomberg so politically successful, however, were their abilities not simply to neutralize their natural opponents but to incorporate them into their coalitions.

Mamdani hasn’t officially won anything yet—and if 1953 and especially 1977 and 2001 are our models, this election may not be over yet. If Zohran Mamdani does ultimately become not just the next mayor, but the generational mayor that history has teed him up to be, New York should expect last night to be only the first of many surprises.

Fight and deliver. 😂

Now I would read more words about this. Tell me more about these mixed coalitions!