It’s barely May and it’s already election season in New York. Like any exile with an unhealthy attachment to the politics of my homeland, I’ve got a few thoughts.

I first sat down to write up my theory that history strongly hints that this will be a generationally important election for New York. The world will now have to wait for that hot take because I got distracted by downloading the entire Cast Vote Record from the 2021 Democratic primary—every single ranked-choice ballot, anonymized.

It’s an incredible resource but required a lot of cleanup to be legible, much to the chagrin of my laptop, which doesn’t seem to enjoy running multiple filters on nearly a million rows of data. As the spreadsheet revealed both valuable insights and insane voter behavior—I’d love to meet the Upper West Side voter whose ballot read: no first choice; no second choice; third choice, Andrew Yang; fourth choice, Shaun Donovan; no fifth choice—I got distracted yet again, this time by a curious bit of legislation I came across while browsing the New York State Assembly website, which I must have visited in a fugue state because I have no recollection of how I got there.

On April 11, a member of the Assembly introduced a bill making changes to a section of election law dealing with minor political parties, which can play a major role in elections in New York—including, very likely, in this mayoral race. New York is one of only two states that allows fusion voting: a candidate can run in the November general election on the ballot lines of as many parties as are willing to nominate them and all the votes received on any of the lines will count towards their total.

This new legislation, Assembly Bill A7829, piqued my curiosity because it’s attempting to change a recently adopted law that has already solved a very real problem. Here’s that section of the law as currently written, adopted in 2021.

§ 6-146 6. A person designated as a candidate for two or more party nominations for an office to be filled at the time of a general election who is not nominated at a primary election by one or more such parties may decline the nomination of one or more parties not later than ten days after the primary election.

In other words, if a candidate who’s been nominated by any minor political parties loses a party primary and decides they want to drop out of the race entirely, they can now easily do so. This has not always been the case, by a long shot.

Before 2021, it was a lot harder for a candidate to stop running: they had to die, move out of New York, which is a kind of spiritual death, or agree to be nominated for a different office, which led to a convoluted process in which live New Yorkers were nominated for random elections they very much hoped they wouldn’t accidentally win.

In New York, an inactive candidate is also more than an inconvenience for a political party—it can be an existential risk, especially in statewide elections, when a party needs to receive a certain number of votes on its ballot line to keep the line for future elections and remain an ongoing political concern.

In the years before §6-146-6 was adopted, there were two notable examples of a minor party desperately trying to get a candidate off their ballot line and having no easy way to do so. Incidentally—or not?!—both examples prominently feature the current leading candidate for mayor, Andrew Cuomo.

In 2002, the Liberal Party had already given their ballot line to Cuomo when he decided, a week before the Democratic primary, that he actually did not want to be governor just then and wasn’t going to run anymore. As the New York Times reported at the time, Cuomo did not avail himself of any of the three options which then existed for being removed from the Liberal Party line:

The party, which designated Mr. Cuomo as its candidate four months ago, let a midnight deadline pass to nominate him for a State Supreme Court judgeship, one of three ways, aside from death or an out-of-state move, for candidates to be removed from the ballot.

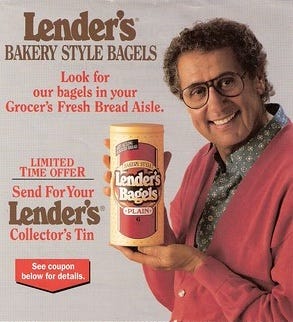

The Liberal Party had been one of the most successful minor parties in New York, starting out as a reform movement in the 1940s before later carving out a niche for themselves as the preferred method for Democratic voters to vote for Republican candidates, including Mayors John Lindsay and Rudy Giuliani, without reneging on their solemn pledges that they’d move to the Midwest and eat frozen supermarket bagels for the rest of their lives before ever voting on the Republican line.

Despite their long history, the Liberal Party still needed 50,000 votes in the 2002 election for governor to maintain its automatic ballot access and status as a functioning political party. But when Cuomo couldn’t easily get off their ballot line, he didn’t. His zombie candidacy got 15,000 votes and the Liberal Party went defunct.

In 2018, the Working Families Party had its own brush with death when they gave their ballot line to Cynthia Nixon, who then lost the Democratic primary to then-Governor Andrew Cuomo. Unlike the ideologically flexible Liberal Party, the Working Families Party operates more like a left-leaning pressure organization within the broader Democratic Party universe and had no interest in having Nixon contest the election on their line, potentially playing spoiler and helping elect a Republican.

As with Cuomo in 2002, the only way at the time to remove Nixon from the WFP line that didn’t involve her leaving New York and/or the earthly plane entirely was to nominate her for another office, in her case an Assembly seat held by a fellow progressive Democrat—who was not happy about it.

It was certainly with these two stories in mind that two WFP-aligned state legislators in 2019 introduced a bill to allow a candidate to simply drop their minor-party line after losing a party primary—the first attempt at §6-146-6. That bill died in the Assembly, and the next year, Cuomo pushed through changes to New York’s ballot access laws that have made it significantly harder for minor parties to gain and maintain ballot lines.

Undeterred, the same two legislators reintroduced their bill in 2021. This time the bill passed, Cuomo signed it, and the new law almost immediately worked as designed. City & State New York describes what happened when the Working Families Party needed to remove two candidates from their ballot line in 2022.

A new law in the state simplified that process significantly by giving third party candidates the option to decline the designation within a handful of days of losing a major party primary. No placeholders and upstate judicial races needed. Williams and Archila made use of this new law, allowing the WFP to nominate Hochul and Delgado in their stead. Along with ensuring that the two progressive candidates would not split the Democratic vote, having Hochul on their line all but ensures that the WFP will maintain its automatic ballot access by attracting enough votes.

The law did exactly what it was supposed to—so why change it now?

It’s been a while since I could execute the world’s least socially successful party trick and name every local elected official in New York City, so I had to look up the author of Assembly Bill A7829. Latrice Walker, the chair of the Election Law committee, represents Brownsville in the Assembly—and was one of the first state legislators to endorse Andrew Cuomo in the June primary for mayor. Could this be evidence of, dare I say it, skulduggery?

It doesn’t seem like it—Walker has often run on the Working Families Party line, she supported §6-146-6 in 2021, and, more to the point, I couldn’t figure out how her bill would help Cuomo. And believe me, I tried.

But what does her bill do exactly? Here’s what it says.

6. A person designated as a candidate for two or more party nominations for an office to be filled at the time of a general election who is not nominated at a primary election by one or more such parties may decline the nomination of one or more parties not later than [ten] SEVEN days after the primary election IS CERTIFIED.

§ 2. This act shall take effect immediately.

Parsing the various deadlines set by New York’s election law is like solving a logic puzzle designed to make you question the very nature of reality. I’d rather not admit how long I spent trying to calculate a date for “not later than the third day after the last day to file the certificate of such party nomination” before realizing the Board of Elections publishes an annual political calendar with all relevant dates.

Assembly Bill A7829 moves the deadline for a primary loser to drop out of the race entirely from ten days after the primary to seven days after the election is certified—which in 2021 was four weeks after the primary. Instead of ten days to make a decision, it appears a candidate would now have about five weeks.

It’s a mystery to me why the author’s published justification for the bill claims the opposite.

The electoral process will become more efficient because election officials can complete ballot preparation sooner when candidates have less time to decline nominations.

“Seven days after” a primary election is certified is quite clearly later than “ten days after” a primary election is held. A candidate would not have “less time to decline nominations”—they’d have more. I can’t quite make sense of this discrepancy.

My own imperfect math, with an assist from the political calendar, instead suggests that A7829 would align two conflicting deadlines for minor parties. Now, if a minor party nominates a candidate ahead of a primary, and the candidate loses, the party has two weeks after the primary to replace them on their ballot. But if the minor party doesn’t nominate a candidate ahead of a primary, they have roughly five weeks after the primary to choose their candidate. The confusing intent offered by the author notwithstanding, my reading suggests that Walker’s bill would no longer penalize a minor party for giving its ballot line to a candidate ahead of a primary.

It may in the end be merely a technical change. But bills don’t come out of nowhere and I’d be curious to know who’s asking for this one. It’s worth mentioning that the Working Families Party, which has strongly suggested they will split from the Democrats if Andrew Cuomo wins the primary, chose not to award their ballot line before the Democratic primary—instead encouraging voters to rank four candidates.

Could that decision have been influenced by the tighter timeline set by §6-146-6? Would an extension of that timeline—if that’s what A7829 is in fact offering—have affected the timing of the WFP endorsement? I don’t think it could have any practical effect at this point, but I’ll still note that it would be aggressive but not impossible for the legislature to pass Walker’s bill before the June 24 primary—in 2021, §6-146-6 had passed both chambers by June 10.

If any readers know or know somebody who might have a read on the backstory here—particularly why the justification for the bill so plainly seems at odds with the bill’s actual language—I’d love to hear it. I’ll be back at some point with more thoughts on the election—I’ve got just 942,000 more rows of data to look through.