In politics, indictments usually lead to resignations, but over in my hometown of New York, it’s the proposed dismissal of an indictment that has prompted four of Mayor Eric Adams’ deputy mayors to resign, putting enormous pressure on Adams to follow suit. Under equal scrutiny is Governor Kathy Hochul, who everyone has recently learned has the power to remove Adams from office. Eric Adams is clearly a problem for New York City right now but his removal by the governor wouldn’t be so great, either.

The current chapter of this crisis started with a distant elected executive, the president, allegedly exercising leverage over the mayor to influence local policy. Is the best solution really a different, slightly less-distant elected executive, the governor, exercising leverage over the mayor to influence local policy?

Like any other city, New York was chartered by an act of the state legislature, so it owes its very existence to Albany. New York, of course, is not just any city, or at least that’s what New Yorkers are legally required to proclaim in a public forum no fewer than six times a day. Still, the balance of power is tilted towards the state, as evidenced by the governor’s statutory authority to remove the mayor.

Making use of that power would give the state even more leverage over the city—and there’s already a long history of the state taking advantage of its position to interfere in the city’s charter-granted home-rule power to govern itself.

In a certain, basic sense, New York State is New York City’s landlord. A landlord can’t do whatever they want: they may be able to come into your apartment to fix a shower, but they can’t just let themselves in to take a shower. On a number of crucial policy areas, however, New York is constantly walking into its bathroom to find Albany all lathered up and squeezing the last drop out of the city’s bottle of Duane Reade-brand body wash.

The canonical example here is the 1975 fiscal crisis. Among other things, New York had become more generous with its unionized municipal workforce than its bankers liked. The state took control of the city’s finances for the next decade and was still poking around its books until 2008, which was like your landlord coming over and watching you take a shower, averting their eyes only to rifle through your bills and ask why you’re spending so much on subscription boxes when the fridge is already full of rotting produce from your weekly CSA delivery.

The popular narrative is that this state intervention saved New York and there’s certainly a fair bit of truth to that. After all, New York isn’t always a dream tenant. At times, Albany knocks on New York’s door and asks, “I’m sorry, did I hear roaring coming from your apartment?” And New York says, “Yeah, those are my lions,” and Albany says, “You can’t have lions in this building,” and New York shrugs, “We’ve always had lions,” and hands Albany a four-hundred-year old lion-keeping agreement written in Dutch.

But the policy prerogatives of the city are not always aligned with the politics of the rest of the state. Beyond the fiscal crisis, the state has not been shy about using its natural leverage to “save” the city from its worst (read: most progressive) instincts.

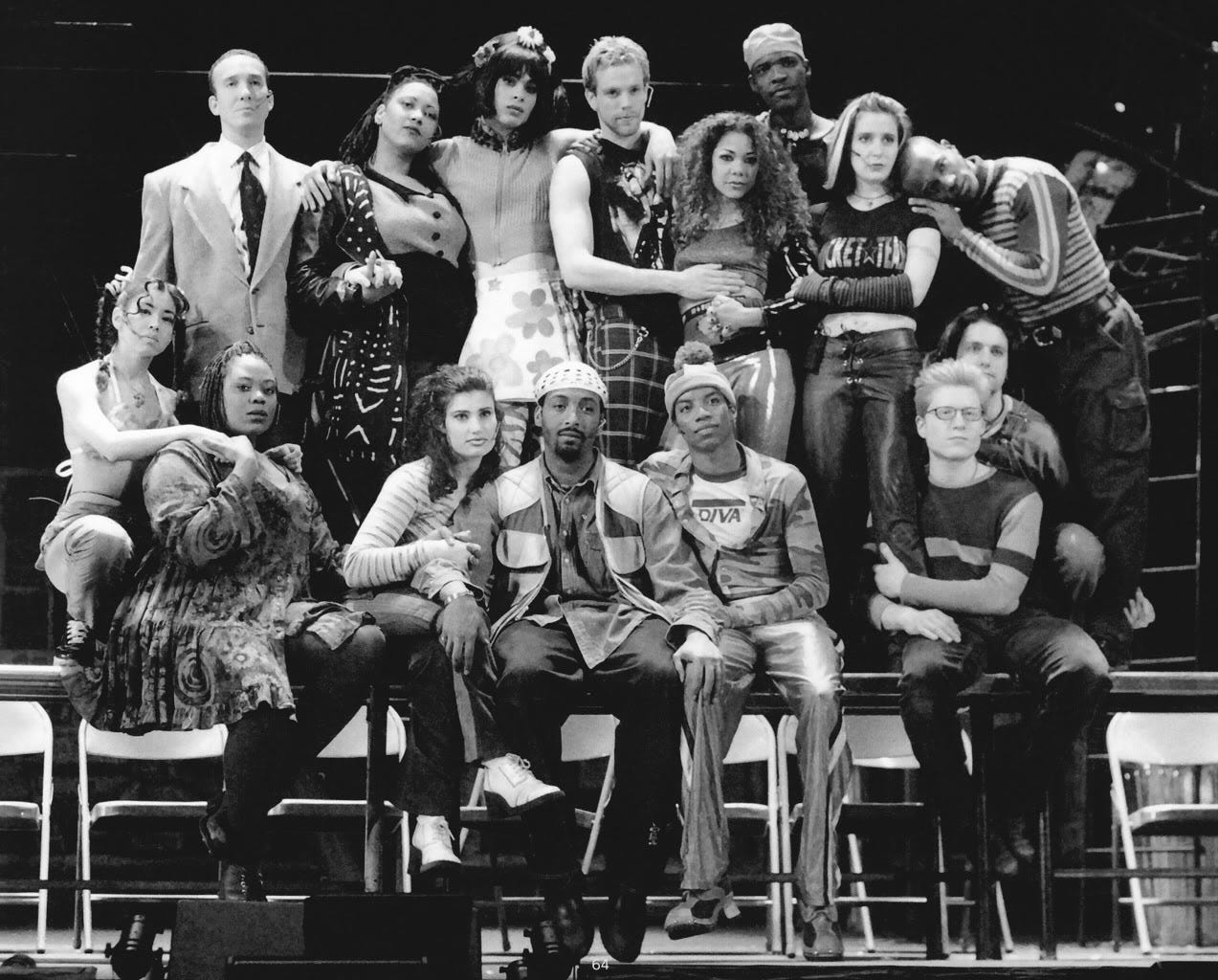

Housing policy is a good example. More than two-thirds of New Yorkers rent their homes. Renting is in many ways a defining experience of being a New Yorker—there’s a reason the most enduringly popular Broadway show about contemporary New York isn’t called MORTGAGE.

About half of New York’s renters live in rent-regulated apartments, but since 1971, it’s been the state that sets rent regulations for New York City. There’s no consensus on whether this has led to more housing development and greater economic growth or contributed to a housing crisis that’s made even tiny apartments with the proverbial toilet in the kitchen unaffordable to everyone but crypto millionaires and NYU students from Dubai.

What’s clear, however, is that a set of crucial policy decisions are not being made by the local community most affected by them. It’s a clear violation of the principle of subsidiarity, an academic-sounding word I learned from my sources in the academy. The state legislature has recently adopted more tenant-friendly rent regulations, but the power structure remains the same: after 1971, the city couldn’t enact its own rent policy even if it wanted to.

A cynic might say that the state’s intrusion into the city’s real-estate issues—land-use policy is historically left almost entirely to local communities—is a pretext for state legislators to solicit campaign contributions from real-estate interests. A less cynical person is probably not from New York.

The subway (and bus) system plays a similarly outsized role in the lives of most New Yorkers, but the city doesn’t have operational or financial control over the system. The city didn’t do an amazing job running mass transit: they never wanted to raise fares but always had to raise wages under the threat of crippling transit strikes, leading to operating deficits and depleted capital budgets for maintenance of a system that was already old by the 1950s.

In the late 1960s, the city came up with a solution—using revenues from tolls on the city’s bridges and tunnels to pay for mass transit, which is similar to the new financing scheme for congestion pricing, actually—but needed permission from the state to implement it. The state liked the idea so much they took it for themselves and ended up in control of everything.

Now, through its ability to set (i.e. raise) fares and tolls, the state-controlled Metropolitan Transportation Authority essentially has taxation power over New York City. It’s enough to make a New Yorker throw on a tricornered hat, board the M8 bus and scream “DON’T TREAD ON ME!” until they appear as a light-hearted anecdote in the New York Times’ Metropolitan Diary.

And then there’s education. For a long time, the state’s primary role in New York City public schools has been chronically—and illegally, as the courts ruled in 2007 after a thirteen-year battle —withholding billions of dollars from the system. Yet mayoral control of the New York City public school system requires state authorization, so every few years, the mayor must travel up to Albany and ask the legislature to extend that authorization.

All across the country, state governments are meddling in local schools to advance political agendas that have nothing to do with education. To its credit, Albany hasn’t done the same—at least not yet. But it could! I don’t think most New Yorkers would be thrilled that the governor and state legislature could mess around with a public school system that has been one of the most successful institutions for social mobility in the history of the country.

There’s an argument to be made that the need to balance the interests of the city and state have led to better policy outcomes. In some cases, that might even be true. But what’s most corrosive about this arrangement is that the misalignment between responsibility and accountability has come to benefit elected officials at both the city and state level, at the expense of the New Yorkers who are constituents of both.

When difficult issues arise—Why does the subway keep costing more but getting worse?—the state provides a useful villain, which can help the city’s own politicians avoid hard decisions. And what happens when the useful villains are actual villains? Eric Adams being removed by Kathy Hochul doesn’t sound that horrible. But imagine that power in other hands, over other mayors. In other words, it’s a bad precedent.

The last two governors elected before Kathy Hochul both resigned in disgrace. From 1994 to 2015, four of the five men who served as leader of the New York State Senate have gone to prison. It’s been a bipartisan affair: two were Republicans, one was a Democrat, and one tried to be both at the same time, a hybrid political affiliation he seems to have invented solely to pursue corruption more efficiently. During that same time period, only one man served as speaker of the New York State Assembly, but he apparently missed all of his buddies and also went to prison.

Not every powerful person in Albany is a crook or a creep. Some are both! Others, like Kathy Hochul, might seem basically fine but there will be worse governors using the threat of removal to pressure better mayors than Eric Adams. This doesn’t seem like the moment to be sanguine about executive overreach anywhere in America.